Nkateko Masinga is a South African poet and 2019 Fellow of the Ebedi International Writers Residency. She was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in 2018 and her work has received support from Pro Helvetia Johannesburg and the Swiss Arts Council. Her written work has appeared in Brittle Paper, Kalahari Review, the U.S. journal Illuminations, UK pamphlet press Pyramid Editions, the University of Edinburgh’s Dangerous Women Project, and elsewhere. She is the Contributing Interviewer for Poetry at Africa In Dialogue, an online interview magazine that archives creative and critical insights with Africa’s leading storytellers.

In 2017, two of my poems were translated from English to French by Alliance Française de Lagos and published in the 2017 issue of Ake Review. I cherished this book and took it everywhere I went. A year after this publication, while I was in the United States for the Mandela Washington Fellowship, a French-speaking friend from Burkina Faso asked to read some of my work: she is a poet too, but only writes her poems in French. When she told me this, I ran excitedly to my room to fetch the treasured Ake Review. I showed her the poems in French, side-by-side with the original poems, which are in English. She started by reading the English poems and then the translations. Her response was “These are not the same.” My face fell. What did she mean they were not the same? She went on to explain that some of the figurative expressions in my poems had been interpreted literally in the translations. I sighed with the understanding that my work had fallen prey to the overused idiom, “lost in translation”, which, according to The Free Dictionary’s definition, is:

‘Of a word or words, having lost or lacking the full subtlety of meaning or significance when translated from the original language to another, especially when done literally.’

The scenario with my friend from Burkina Faso led to further conversations with other French-speaking friends. One of my best friends, who is also the illustrator of my first three poetry chapbooks, is a French-speaking person from D.R.C. He was the first to ever tell me that the French spoken in D.R.C is not the same as the French spoken in France. Could this also apply to D.R.C and Burkina Faso? If my Congolese friend were to read the poems in Ake Review, would he come to the same conclusion: “These are not the same”? From conversations with my friend from D.R.C and with Congolese Mandela Washington Fellows, I also learnt that D.R.C and Congo Brazzaville are two different countries. Here is what theculturetrip.com says about these countries:

‘The Republic of Congo (French: République du Congo), also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic, West Congo, the former French Congo, or simply the Congo, is a small Central African country. It is bordered by five countries, one of which is the Democratic Republic of Congo situated to the east of Congo-Brazzaville. Congo-Brazzaville was formerly colonized by the French. After gaining independence the country officially became the Republic of the Congo.

The region that is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo was first settled about 80,000 years ago. The Kingdom of Kongo remained present in the region between the 14th and the early 19th centuries. Belgian colonization began when King Leopold II founded the Congo Free State. The Democratic Republic of Congo gained its independence under the Belgium rulers in 1960. After its independence it became known as the Republic of Zaire between 1960 until 1997. Today this country is known as the Democratic Republic of Congo, or Congo-Kinshasa.’

I now have other questions: do the above excerpts not imply that French is spoken in Congo-Brazzaville but not in Congo-Kinshasa or D.RC? Why does my friend from D.R.C speak French if his home country was colonized by Belgium and not France? Is it because French is one of the official languages in Belgium, alongside Dutch and German? If so, does this mean the French dialects of France and Belgium are different? My partner is a linguistics teacher, but I doubt I would even need to ask him to get the answers to the above, because all I need to do is look at my home language, as well as English. I speak Xitsonga at home, and I know from experience and years of traveling that the Xitsonga spoken in Mamelodi (Gauteng), Bushbuckridge (Mpumalanga), Giyani (Limpopo) and Maputo (Mozambique) are all very different. The same goes for English everywhere. Is this the right time to mention my secret fascination with the Australian English accent? Or that I came home from the U.S with the inability to speak properly? I now pronounce the word “here” as “heerrr” instead of “heeya.” What did America do to my tongue?

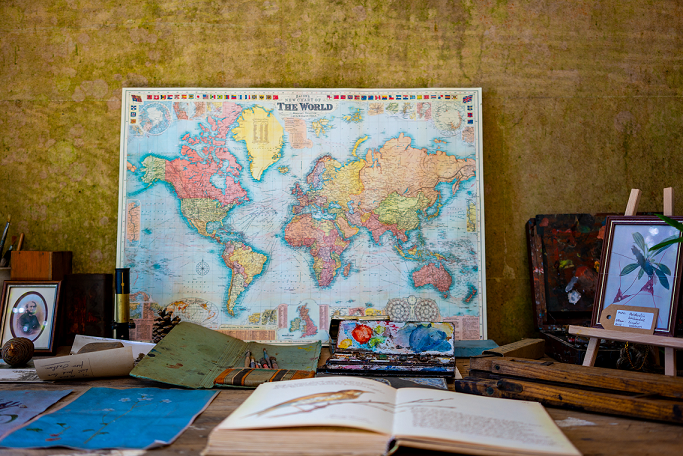

All of this has gotten me thinking not only about language and its intricacies but about existing translated poetic work, from English to other languages, and vice versa. What makes a good translation? What is lost when we translate in the absence of the original writer, and can we correct this through dialogue? I ask about dialogue because I currently work with a team of literary interviewers who have conversations with writers all over the continent of Africa, conversations which would not be possible if we did not have a common language to communicate in. Had it not been for English as a common thread, would we be having dialogues in the same way? Also, are there writers whose countries we do not reach in our work because they are Francophone and not Anglophone? A Mandela Washington Fellow from Benin once told our class (at Wagner College) that she had taught herself to speak English so that she could apply for the fellowship and other opportunities open exclusively to English-speaking people.

Apart from the above, in what other ways does language restrict us from communicating with each other not only as fellow humans but as fellow artists and writers? Does our willingness to engage with the work of an artist depend on the language they communicate in? If we were all painters this would not matter, but for those of us who use words to create images, do we keep the audience only of those who can understand what we are saying? Before we can speak of an “open Africa” with no borders and no visa restrictions, can we have a conversation about the borders created by language? How do we go from being “lost in translation” to being found (as Africans, regardless of how or what we speak) in it? As poets, whose responsibility is it that our work is accessible to everyone, regardless of language?

I was recently approached by an Indian writer who expressed interest in translating one of my poems to Bengali. It was all going well until he mentioned that he was struggling with my name (Nkateko) because in Bengali, the letters “N” and “K” are never used to begin a word. Failing to understand how this was possible, I told him to translate the poem from English to Bengali but to publish my name as it was because it is not an English word and does not form part of the translation. He then explained that Bengali does not have a symbol for the “Nk” sound at the beginning of a word, so it would be quite difficult to publish it, regardless of the poem itself being publishable. In hindsight, I quite like that my name, such an important part of my identity, is unimaginable or impossible in another part of the world, and yet my work still managed to reach those foreign shores.

- Living In Colour – #Nkateko - June 15, 2020

- Found in Translation – #Nkateko - December 9, 2019

Leave a Reply