At first, the idea of sharing it with girls in our class never came to mind; but, soon the spirit of youth began to spring in our souls, we began to hear the whispers of our hearts and our minds believed it was love.

So when in the psych ward in 2016, words leaked out of me like pus, I did not worry about the boundary of this or that. Cows and pigeons filled the room from the fields of childhood. I let the sun be a coin, did not resist seeing the moon’s arc as a shiny scar in the night sky.

Through poetry, I was able to express the inexpressible, to give voice to the emotions that threatened to consume me. I wrote about love, loss, longing, hope and the universal human experiences that connect us all.

I’ve carried that mindset in every piece I write, I never use my phone to write. Instead I lock myself away with my laptop that only has Microsoft word paired with a thought-racing mind. Most times before I write a good poem I’m very hungry, I probably wouldn’t have eaten the whole day. Me being uncomfortable pushes my brain to lock in, not get distracted and finish the work so I can be comfortable again.

Véronique Tadjo is a renowned Ivorian novelist, poet, and writer. At 69, her work stands as a powerful testament to her rich heritage and the influence of the French language, in which most of her writing is rooted and written. Her work has been translated into over 20 languages, but as English author Samuel Johnson observed, “the beauties of poetry cannot be preserved in any language except that in which it was originally written.

Since I was born, daddy bought us books. He was a writer himself, writing stories in notebooks that ended up in corners of the house, unpublished. Had my father been born in more recent times, he’d be a great writer, I think.

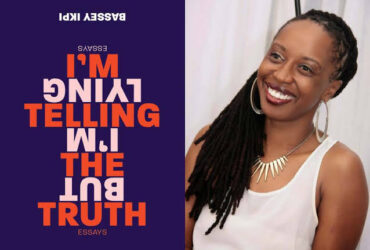

Bassey Ikpi still identifies as a writer though she has referred to herself as an “ex-poet”. She has recently clarified that poetry was simply the conduit through which she could articulate all the emotions she failed to understandably express. Now, she says, she is healthier than ever and is interested in publicising wellness as a possibility, as a lifestyle.

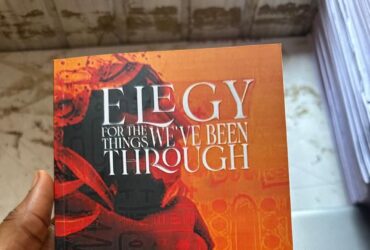

Although a chapbook of very short poems (which seems like the poets’ attempt to test the water of critical reception), part of the aesthetic appeal of the collection is the poets’ use of language.