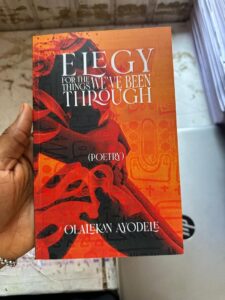

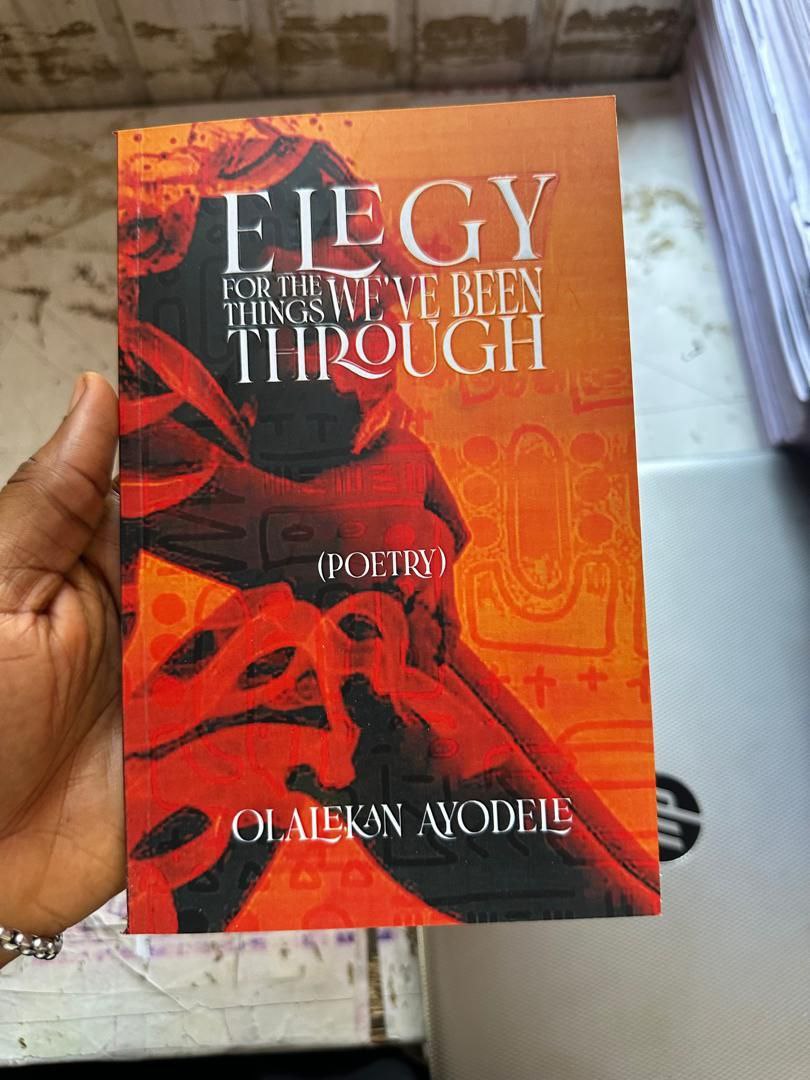

Language, in its most basic definition as a systematic means of communication, often becomes an encumbrance when humans are involved in intercultural relations. Even between people of the same culture, language often proves to be insufficient. However, the language of poetry is not so. Foucault defines the poet as he “who, beneath the named, constantly expected differences, rediscovers the buried kinships between things, their scattered resemblances.” Beyond the metaphor level, the language of poetry is an adhesive; it inspires recognition, connection, and empathy. It is this empathetic function that Olalekan Ayodele’s collection of thirty-seven heartfelt poems of varying structures and length, hinges upon.

One thing we have in common is the world. The “world” as is represented in Ayodele’s poetry, is an adversity—a tyrannical force that oppresses its inhabitants in various, innovative ways. One thing we have in common is this adversity, so that even when the first-person singular pronoun “I” is used in contrast to the “we” of the collection’s title, it does not alienate the speaker from the reader. In some cases, the reader assumes the role of the speaker. In the initial verse entitled “Glass,” we find lines like: The world has taken my memories away/ all the gaps in the songs I love remain empty/ with darkness. And, But the world, the world swivels a knife at the thickness of my skin… This verse presents a poignant reflection on the multitude of afflictions that humanity faces, not aiming to impart new knowledge but rather to portray the devastating experiences that shape our existence.

While “Glass” ends on a hopeless, “shattered” note, the succeeding poem “A Fortune for Distress” is a breath of fresh air. For the speaker, and equivalently, for the reader, art and language become a way of making sense of a distressing reality—this is evident in lines such as: She says language is the only protection thick enough, to cover the turmoil of the world. And, My mother understands, most of / music is worship, the remains /were aesthetics large enough to / move the legs through a tap dance.

Quite remarkable is Ayodele’s keen attention to space. He fulfills what theorists such as Michel de Certeau, Henri Lefebvre, and Edward Soja, amongst others, refer to as “lived space”—the perceived, emotional, and sensory experience of space, as conveyed through language and imagery, evoking a sense of place, memory, and being. In “The Urgency of Lagos Life,” the first line My country is sagging grants an image of a state undergoing deterioration, while the latter lines invite us into the hubbub of the city; it speaks of the “music of the mechanic’s spanner,” the “exhausts of tired trucks,” and the people “busy with the sweat and dust of living.” Lagos is so busy with the rigors of life that the speaker cannot hear the racing of their heart. Despite the mention of “light,” “cuisines,” and “music,” the poem manages not to betray any form of pleasantness whatsoever, and one is forced to remember that all of this vivacity is still situated in the sagging country of the first line.

In “From What the World Remembered and Told Us,” Ayodele contextualizes insurgency within a traditional framework by adorning his lines with vignettes of everyday life throughout the poem’s three stanzas. Words such as “ayo,” “ankara,” “amala,” “lawn grass,” and “laughing” effectively construct a scene of normalcy and harmony, which is abruptly shattered first by the intrusion of a bullet into the boy’s body and ultimately by the news of death.

The first stanza begins thus:

When the news of the death reached our ears/We were under a neem tree playing ayo,

Second:

When the news of the death reached /His mother’s ears, she was turning Amala for the family.

And the last:

They said he was wearing a brown

Ankara with a smile almost touching

the tribal marks on his cheek. They

said when the bullet touched his skin

he was laughing, his teeth as even

As a lawn grass.

Here, poetry not only rediscovers the buried kinships between things; it sparks recognition in the reader and introduces the unfamiliar to the familiar by aptly portraying space through language as if to say, “This is what/where I come from.”

Ayodele’s collection oscillates between two distinct tones and two distinct styles. While poems like “A Broken Country as Portrait,” “Constitution for Bad Governance,” and “Who Do We Show Our Wreckage?’ embody the truths and music of our despair as humans and as inhabitants of Nigeria, poems like “To the Man I Have Become,” “First Rain,” and “Of Delicateness and Kindness” happen with a sense of absolution, hope, and healing. In style, Ayodele commands a switch between the free verse and some musical traditional forms, such as the Ghazal in “Ghazal for Despair.” A good example of the tonal switch lies in the beginnings of “From What the World Remembered and Told Us” and “Of Delicateness and Kindness.” While the former begins with disruption, the latter begins with restoration by announcing the end of a war and promising the colors of the Gėlėdė festival. Ayodele offers both darkness and light, acknowledging sorrow while pointing toward hope.

By the end of the Civil War we were collecting

Snails and periwinkles for the Gėlėdė festival… (Of Delicateness and Kindness)

Through language, Ayodele’s “Elegy” not only performs a collective candlelight for sorrows past; it initiates an introspection into these hurts and their causes and also hints at the possibility of peace and healing through art, language, and connection.

In an alternative universe

Where every ending is a

Door to something other

Than the beginning, someone

Would be waiting, one arm warmth,

The other tenderness, to receive

Your poems….(“How to End a Poem in Peace”)

Chinaza James-Ibe is an award-winning poet and editor, who writes from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

Leave a Reply